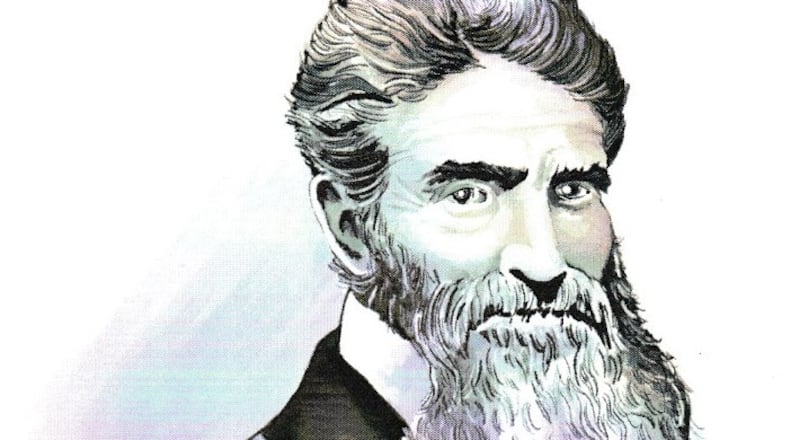

Every time a $5 bill is exchanged, Americans are reminded of the pivotal role Abraham Lincoln played in American history. But Dennis Frye argues that Lincoln would never have made it to the Oval Office in 1861 were it not for John Brown.

That’s just one of the reasons the retired chief historian of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park considers Brown one of the few transformative figures in American history.

Brown’s failed attempt to steal weapons from the United States Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Va., in October of 1859 was to have been the first act in the radical abolitionist’s war against the United States government for aiding and abetting a sin against humanity: slavery.

“Brown believed that enslavement in its own right was a form of death, is a form of murder,” Frye told his Zoom audience. “If you don’t have freedom (Brown argued) a piece of you is being killed every day.”

Having already violently opposed slavery’s spread to western territories, Brown set his sights on Harpers Ferry intending “to impose his own sanctions on slave owners” Frye said – men Brown considered the oligarchs of his time.

Brown’s plan was to take weapons into the mountains and send small guerilla forces on raids to liberate slaves plantation by plantation — on a scale the Underground Railroad could never achieve.

An owner deprived 50 slaves with a value of $1,000 each “would be bankrupt, just like that,” Fry explained. Enough bankruptcies might undermine the value of slaves in the way today’s sanctions have reduced the value of the ruble — “to the extent,” Frye said, “that it was no longer valuable to own slaves.”

Brown’s hoped-for result was the collapse of the slave market and mass liberation.

Brown’s capture at the hands of then United States Army Capt. Robert E. Lee, both ended that and eventually achieved Brown’s goals in another way.

After decades in which the majority consensus about the future of slavery had slowly been shredded, the man who had been too radical for most abolitionists,” “was a sensation everywhere,” Frye said.

In the six weeks between his arrest and hanging “Brown literally transforms America,” Frye says. “As an individual, he forced the United States of America no longer to debate slavery — no longer to talk about slavery — but into taking action on slavery.”

This leaves the Democratic Party “polarized and split,” Frye said, which led to the election of the man on the $5 bill.

Black voting rights and a shifting white majority

Shortly after 200,000 African-American troops helped the Union to secure victory in the Civil War, Nicole Etcheson said, a majority of “white Americans, as well as Black Americans” united in the belief that those who had braved bullets for their country had earned the right to cast ballots.

But the Ph.D. in history at Ball State University added that the memory of the soldiers’ sacrifices faded with those of the war, and there began a history of the disfranchisement of Black people that clings to us today.

As president, former Union General Ulysses S. Grant, who was well aware of all Union soldiers’ sacrifices, sent troops south to suppress the Ku Klux Klan and its attacks on Black rights.

Soon after, however, the federal government largely abandoned the cause, and Etcheson deferred to the work of Pulitzer Prize winning historian Eric Foner’s account of what happened next: Confederate veterans refilled the ranks of a Klan that, as the “military arm” of segregationist South, used beatings, lynchings and arson to keep Black citizens from voting.

In doing so, they confirmed African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ assessment of voting as “the one great power by which all civil rights are obtained and enjoyed under our form of government.”

As the turn of the 20th Century approached, white veterans on both sides of the conflict reconciled with one another in a move that helped to heal the nation, but at a cost.

Because it was easier to “create good feeling without getting specific about what the sides fought for,” Etcheson said, the lived history of centuries of Black subjugation and the war’s critical role in emancipating them was whitewashed — along with the contributions of Black soldiers to the cause.

A complicated culture war then ensued. The defeated South, whose men felt guilt over losing the war and having been unable to save their women from marauding Northern armies, was fictionalized in D.W. Griffiths’ movie “Birth of a Nation,” as members of a Ku Klux Klan that protected Southern women.

She offered as counterpoint the 1990 movie Glory, in which Denzel Washington, as a member of the African American 54th Massachusetts, speaks the line “we’re men, aren’t we” the night before the unit’s attack on Fort Wagner.

“That is the overall theme of the movie,” Acheson said: “That the Civil War was the opportunity where African-American men could go from their status as enslaved … to proving manhood ... through courageous service.”

Asked toward the end of her presentation whether she sees a connection between past use of poll taxes, literacy tests and other voting suppression measures and recently imposed voting laws, Etcheson said yes. Both, she said, use a seemingly neutral requirement that, when carried out, favor one class of voters over another.

All Southern voters had to pay poll taxes at one time, she said — but at a time when poorer African-American voters were much less able to afford them.

Why the Emancipation Proclamation disappoints

In his second inaugural and Gettysburg addresses, Abraham Lincoln delivered speeches of an artful, literary and inspirational quality now written in stone in the memorial erected in his memory.

But in a presentation on the decidedly drab Emancipation Proclamation, Wittenberg University History Professor Thomas Taylor says we see “Lincoln lawyer” trying to thread constitutional, political and military needles in a way that would allow him to take care of the business of winning the war while ending slavery and saving the Republic.

The puzzle the president had to solve includes two realities people tend to overlook today:

- In 1860, slavery was constitutional, which the president was powerless to change.

- Slavery existed in four Union states that could not be alienated because, should they switch sides, Washington, D.C. would be surrounded by a Confederacy that had more citizens than the remaining “dis-United States.”

Taylor said Lincoln additionally was hemmed in by two constituencies: Northern Democrats who supported the war to preserve the union but not to emancipate slaves; and people in the South’s own complex political landscape who might favor a return to the union.

But as chances for compromise disappeared in the mud and blood of war, emancipation became politically more attractive, a deal Lincoln hoped to sweeten by offering to sell federal bonds to buy the freedom of the nation’s slaves. The stick that accompanied the carrot foreshadowed what was to happen: Slave owners’ loss of all of their slaves — representing $4 billion of “assets” — without a cent to show for it.

When the border and Southern states rejected that plan and draft riots broke out in New York, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation sought to end slavery as a means to restore the union.

Still holding that he could do nothing about slavery in peacetime, he argued that as commander-in-chief in a time of war, “I may in an emergency do things on military grounds which cannot be done constitutionally by Congress.”

Threading a political needle, the proclamation freed slaves in the Confederate states only — the states in rebellion. This aimed to deprive the South of slave labor used in the war effort but left slavery in the Union’s slave states, whose support was needed to win the war.

The proclamation also controversially opened the door to African-Americans serving in the Union Army, which enraged southerners who thought it a depraved act, but helped to address the manpower issues in the Union ranks during a time when volunteers were in short supply.

Said Taylor: “There are folks that argue (the addition of African-American soldiers) may well have won the war for the Union Army.”

The proclamation also was “an international relations coup,” Taylor said, because anti-slavery sentiment in Britain made it “politically impossible for people in the higher levels of the British government to consider support of the Confederacy, a big plus for the Union.”

“People who are disappointed by the Emancipation Proclamation, I certainly understand their disappointment,” Taylor said, because it lacks the grandeur of his other addresses.

But, he said, Lincoln “has to balance all these issues in a way really nobody else had to” — while fighting a war.

About the Author