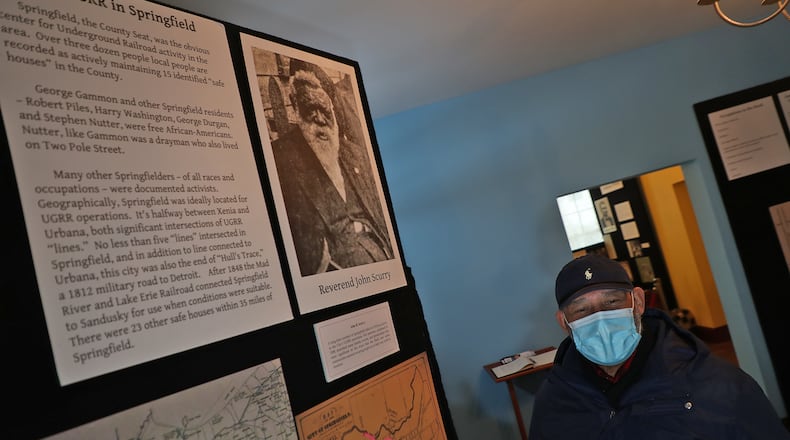

From May 3 to June 28, 1908, the Springfield Daily News and Press Republic published a series of letters by the Rev. J.R. Scurry that details the rich, complex history of local connections to the Underground Railroad. A graybeard at the time of his letters and a shoe repairer living on Central Alley, Scurry had been a conductor on the Underground Railroad in the late 1850s and early ’60s.

That had put him front and center both in American history and the small army of courageous blacks and whites who defied the laws of the time to smuggle desperate escaping slaves, or fugitives, from the deep South to freedom in Ohio and Canada.

Scurry was not only a “quite a dude among my people,” as he puts it, but well-connected with the white community, in part through the errands he ran for the Wallace Drug store.

A talent for story-telling that surely made him likeable to all shines through in his stories, some dead-serious and some falling down funny. Together they would make a fine script for a Netflix series but will appear in condensed and edited form for the next four weeks in this column to help celebrate Black History Month.

Note: The text includes words now considered to be dated in referring to Black Americans. We have preserved them, in most cases, to be consistent with the usage in J.R. Scurry’s time and his writing voice.

By J. R. Scurry

Uncle George (Gammon’s) house on what is now called Winter street, can show you the remains of some of its places of secreting fugitives in the cellar and attic. Three of the girls are still living: Mrs. Margaret Bowser, Mrs. Sadie Banks and Mrs. Cornelia S. Henderson.

These ladies can tell of the many mornings they got out of bed to find themselves without a change of clothing. Aunt Sallie, their mother, had furnished clothes and food for a train load of fugitives during the night.

But the Gammons were not alone.

The escape of the coal-black negro

To improve the chances of catching escaped fugitives, authorities sent posters ahead, the same as they would for a horse or cow that was stolen or strayed. And in 1854, a poster arrived in Springfield about coal-black negro weighting 200 pounds, height six feet, one hand badly mangled by dogs -- perhaps entirely off. Reward: alive, $1,000; dead, $200.

We learned the fugitive had killed one of his pursuers and three dogs involved in the hunt.

Some two days after the wanted poster went up at the courthouse, we got information that the master and United States marshal of Cincinnati were at the old Werden House, at the corner Spring and Main streets. So, everybody got busy, some watching for the fugitive and some keeping eye on the master.

The fugitive was compelled to lay in wait until his hand was cared for, which had to be amputated, in Cincinnati.

The pursuers had been held over here by Old George McCoy, telling a story of how some colored man had killed a hundred dogs and half dozen white men was coming this way. This caused them to put a little confidence in old George, so they began to question him as to who the fellows were that helped the runaways.

Yes! He knew them all, but because he was afraid to tell anything, he would show them. So, for a consideration of five Mexican dollars, he agreed to lead them where they could way-lay the fugitive when he got off the train at the downtown depot.

But, the train from Xenia bringing the fugitive had stopped out at a crossroad, three miles out of town and the fugitive was taken to a house on the old Peter Schindler farm.

Uncle Jimmie Wiggins, the bravest man that ever pulled a throttle on an engine, was engineer pulling that train. He had been posted about the situation and so stopped at a place he regularly “wooded up” in those days before locomotives ran on coal. So, nothing seemed out of order.

Old George happened to be there, lent a hand in the wooding up and rode along into town. Jumping off before the train ran into the gates, he ran around the depot and pretended to wait to escort the victims into a trap set.

But by that time, though, the pursuers had tired of hiding behind the weeds of a nearby swamp and had already come up to the depot, where they then learned that a negro with an arm in a sling had already got off. The master and the United States marshal lingered around for several days and then, following more instructions given by old George, took the route to Cleveland, O., in pursuit.

The fugitive soon was transferred from the farm to Uncle Harry Washington’s in Walnut alley, in the rear of William Pyles’ barber shop, wherein the daytime he was hid away in a niche in the wall.

Jim Keemer, a boy raised by Pyles, remembers how uneasy Pyles was for fear slave-hunters would return and find this fellow’s hiding place. Pyles was a warm friend to the work, but to be found out mean not only imprisonment, but the loss of all of his belongings.

(At another time, when a bright boy fugitive was sent, Pyles made Keemer take the boy out of town each night so as not to come in contact with any of the human wolves that were infesting the town.)

In the stowaway for four days with Pyles, the one-hand man went by the way of Urbana on the Underground Railroad to Sandusky, where the Moore brothers (barbers) took charge of him, landing him in Canada.

He had given no one his name, which always was done when they stopped so those who helped them could be told by letter the fugitives had reached freedom.

But some years after, the one-hand man came back to Springfield and gave us quite a visit.

Today’s final story provides a look at the logistics involved in arranging for escapes along the Underground Railroad and how those involved became a part of community history.

The legacy of two hogsheads

Two hogshead barrels, supposed to be filled with sugar, were shipped from New Orleans, but at Louisville one of them was changed. The hogsheads went on to Cincinnati and a certain wholesale house in touch with the Underground Railroad.

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Both barrels were shipped to Springfield, one to the Baltimore Grocery at the corner of Fountain Avenue and High Street, the other to a barber named Jonah Anderson on Main Street just west of Fountain.

The hogshead was rolled into Anderson’s, opened in proper time, and instead of sugar a man 5 feet 4 inches tall made his appearance. This man was taken in as Anderson’s nephew and learned his trade.

Some seven years afterward, the man had to go to Canada, his whereabouts having been discovered. But his presence is still felt among us. Two of his children are living here now, Isiah and Julia, Mrs. Julia Allen keeping the restaurant next to the Central Engine House on South Fountain Avenue.

NEXT SUNDAY: The dangers of cherry bounce.

About the Author