From May 3 to June 28, 1908, the Springfield Daily News and Press Republic published a series of letters by the Rev. J.R. Scurry, a local conductor on the Underground Railroad. Scurry’s 1908 accounts of activities of the Underground Railroad in Springfield might easily be turned into a Netflix miniseries – one that would not lack for a cast of characters. Today’s fourth installment of this Black History Month series focuses on those characters and the roles played in helping runaway slaves to freedom. One involved the character of the night sky. Note: The original text has been edited.

By J.R. Scurry

August 28, 1859, a splendid Auroral display in the heavens. Whenever anything unusual happened in the skies, my people predicted something was going to happen on earth, during that year. That December 3rd, John Brown was hanged at Charleston, Va., and the anti-slavery sentiment was growing throughout the union with fugitives fleeing in every direction.

Two year came the year of the great Comet, when the Underground Railroad was tested to her capacity, trains pulling out every night. Some with as high as 16 with one train.

In both those years, John Wesley “Dad” Moore worked all day at his trade and conducted a train through the night, including the one with 16. He also was involved the time a group of four fugitives and four girls felt the route through Indiana getting too hot and were taken to a home of a Mrs. Brown just on the outskirts of the town.

The United States marshal and masters tracked them there, but when they arrived, she got a double-barreled shotgun out and told them no white man dare enter that door. When they stepped forward a little later, she called out: “Stay where you is.”

The fugitives escaped through some trickery pulled off with the help of boys from a Quaker settlement, who traded places with the boys, then swapped clothes with the girls. So, in the end, when the pursuers were let in, they found only four white boys dressed as girls. You ought to have seen that old lady shake her fat sides.

When it came to doing a thing up nice and fooling those that were always prying about trying to see what they could see, Robert Woods, brakeman and baggage master, was truly a master.

Bob would make a snug little den out of trunks and whatever express matter he had, hide a black man -- or even more, cover him up and bring him through from Xenia. When the train ran into the depot and the gates were closed, Bob would pull up the door where the things were to be put off, then let the fugitive get off on the opposite side of the car. He’d then wait until everything was clear, and unlock the back gate, where it was an easy matter to get out of sight, for the woods ran down to the round houses.

Aunt Sukey Durgans lived in the little frame house that stood next to the old station house in Spring street. While a slave, she was allowed to go wherever she pleased. She made and sold gingerbread all over Kentucky and even came over to Cincinnati with her sweetmeats. She was of great help to the workers on the Underground Railroad, bearing messages to and from.

Big George Durgans, the dandy hotel porter and car runner, commonly called “Dixie” was a known storyteller. So, in the cold winter nights in whatever hotel, he was seated around a warm fire burning wood, these traveling men would get “Dixie” started and you’d hear some good ones, sure! After hearing one of his stories, one of the men said “Porter, why you ought to make a fortune.” “Dixie” asked why. “Why according to your own account, you’re over 200 years old.” He was also a brave man and by himself helped many a fugitive.

Bat Shavers, would set a dozen fishing lines along the creek from where Mill Run emptied into the creek down to the deep water at Ferncliff. He would then crawl into a hole in a ravine in the cliffs, and take three- or four-hours sleep, the reason he was called “Bat.” He also was a powerful man who never combed his head. You couldn’t get anybody, white or black, to bother old Bat’s fishing lines.

He associated with another queer genius, Andrew Jackson, known in later days as a “Voodoo Doctor.” He married Aunty Betsy Hart, but she couldn’t live with him. He generally slept at Joe Liverpool’s corner, Market and South streets.

Well, a man, two women and a child hotly pursued by master had reached this station on a night too cold and damp for the fugitives to go into Mill Run. So, Bat and Jackson took them through McCreight’s woods and out onto the Urbana Road, keeping a sharp lookout.

With the escaping man loaded down with all he could carry and the women exhausted by the day’s exertions, the child simply gave out. So, Jackson put her astride of his back, carried her part of the way, then Bat the rest. The pursuers reached Urbana before them, but the party was nicely cared for by a white family by the name of Morrow -- father of the well-known Stewart Morrow, who kept the Arcade lunch rooms.

A United States marshal and three slave holders accompanied by William Compton surrounded that old house old frame house on the Clark farm, where the Mechanic Street bridge crosses the Panhandle railroad. Inside were Price, the man who lived there, and seven fugitives.

Telling a couple of pursuers to watch the front door, Compton took another of them round to the back door supposedly to see if he couldn’t get the fugitives to give up. While busting out of the back door, the fugitives knocked the other man to the ground, Compton fell over, too. The stunned fellow had no idea where they’d gone, and Compton pretended he hadn’t seen them run through the orchard into Clark’s big woods.

One morning at the court was a poster reading: “One bright mulatto, can be taken for white woman; one black girl and boy, aged respectively 16 and 18 years. Reward for three persons $1,000; with directions where to write, Paris, Ky.

Not long after, an old time carriage, containing an elderly gentleman, a middle-aged woman, a colored boy of 18 and a colored girl of 16 drove up to the old Werden House. The gentleman registered and claimed to have come from the east for the health of his invalid daughter. Conversing freely about the office that week, he quickly became quite a favorite.

In truth, the old man’s companions were three runaways wanted in Paris, Ky., and the old man was Albert Williams of Cincinnati, one of the greatest of Underground Railroad workers.

He wore his hair cut close at all times, and got it cut by a colored barber while in town. But when working, he wore a gray wig and passed for white. After a week’s stay, a fine rig took the party to Urbana. The fugitives took the Underground Railroad north to Sandusky, then Canada. Williams went back south to Cincinnati for more work.

It was reported that the master of a fugitive was in town and that he had learned the slave was staying at Liverpool’s on the corner of Market and North street. We were being closely watched, but something had to be done.

So, one night a doctor pulled his buggy up to the house, and when he came out, he hung a yellow flag out, indicating a case of smallpox. Two or three nights later, two men with a wagon and a box approached the house, carried the box in, brought it out and drove toward Greenmount Cemetery.

On the way, the “corpse” was taken out and put aboard a train of the underground railway that took on two more passengers at Harmony. The doctor was questioned some about the details of smallpox case told his questioners, “I didn’t wait long to see.”

Versatile Dick Mason, could preach as good a sermon as any of that day and, then again, could play as good a game of seven-up. One Sunday afternoon, he and some other fellows had a game that ran a little late.

Rushing to his preaching assignment, he grabbed his hat and overcoat not knowing one of his friends had slipped a Jack of hearts and a Jack of diamonds in a pocket. While preaching, Dick pulled out his handkerchief to wipe sweat from his brow and out dropped the two cards.

Living up to his nickname, Dick told the congregation the Jack of diamonds represented riches and evil and the Jack of hearts for religion or men’s souls, which God wants. He was just as versatile during one of our busiest weeks, when we steered 70 to freedom.

One of those fellows in the kidnapping business belonged to one of Springfield’s best families over on East High Street. He did the spotting for slave catchers out of town. So, we put up a job on him.

By a way of a trap, we managed to put whole gallon of soft tar over his head, running down into his mouth, eyes, ears; and in trying to keep it out of his eyes, he smeared it all over his face. He yelled most pitifully, but everybody was scarce at that time.

After some story was made up about him being robbed, he disappeared and was seen no more about here until the war broke out. He came home on a visit, then went South and joined a company of rebel bush-whackers and tried to see how man “n…..s” (as he said) he could kill. Well, he got killed himself, at least it was so reported.

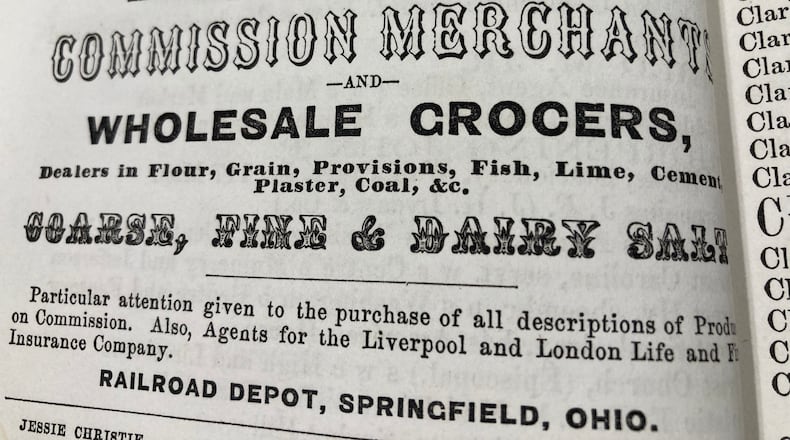

Uncle Steve Nutter, colored, lived in the basement of the United Presbyterian Church, where Carson’s wholesale house now stands. He was a drayman whose stable was in the rear of the big reaper shop and was called on for special duty when a well-known colored man among us meant to betray a goodly number we had in hiding.

At the corner of Spring and North streets, we tied the man’s hands together and put his arms around a gate post so Uncle Steve and others could read the law to him in the shape of 50 lashes with a blacksnake whip. When it was over, the whip went to Uncle Billy Roberts, the fastest runner among the crowd, to whip this fellow out of town. Uncle Billy only got to hit him once. We withhold the name of this fellow for reasons best known to the Order of the Underground Railroad.

Part I: Sunday, Feb. 7 - The Underground Railroad: The escape

Part II: Sunday, Feb. 14 - The Underground Railroad: The dangers of cherry bounce

Part III: Sunday, Feb. 21 The Underground Railroad: What Dred Scott wrought