“No one wants to leave their native country,” said Dady Fanfan, a Haitian real estate agent who came to Springfield in 2020. “But a lot of bad things are happening right now because of the gangsters.”

To find work in an area with affordable housing.

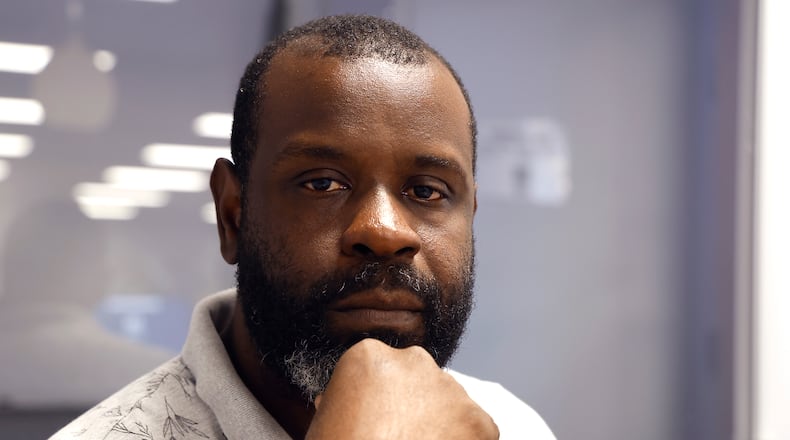

“We’re working here, we’re paying taxes here. We’re just trying to pursue a better life. We come here to work and to get what we want, not to get something we don’t work for. We work to get a better life. That’s why we come here,” said Marco Petit-Frere, speaking through an interpreter at Clark County Combined Health District last week.

To build a community.

The immigrant population here today has become the subject of national controversy, amplified by debunked claims by former president Donald Trump that Haitians are eating people’s pets. Misinformation is running rampant, spreading fear in certain segments of the community and overshadowing discussion of how to address real challenges caused by the sudden influx of a population with particular needs.

This story is about how this population came to live here, and the role that federal policy does play.

Reporting by the Springfield News-Sun has documented that the influx of Haitian immigrants picked up during the pandemic, when local employers were desperate for workers. Companies saw an opportunity to tap into Haitian communities in other parts of the country — many in those communities were legally in the U.S. and had work permits — to fill that gap.

The population grew rapidly. Rocking Horse Community Health Center data from 2018 showed only three Creole-speaking pediatric patients received services from the center over the entire year. In 2022, that number grew to more than 400. By August 2023 Springfield’s then-assistant Mayor Rob Rue estimated the Haitian population at between 5,000 and 10,000.

Katie Kersh, senior attorney at Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, which provides legal assistance to immigrants in Springfield, said they saw two major waves of Haitian immigrants to Springfield in recent years. The first was in 2021, the year Haiti’s president was assassinated. The second was in 2023.

She said both waves appeared to have brought a large number of new arrivals to the country who used legal pathways to enter and stay in the U.S.

The actions of staffing companies were called into question.

“We know that they are a doorway for these folks to get employment. We want to make sure this is done in a safe way, that there are safe opportunities for them,” Rue said.

The city in September 2023 held a meeting with six local staffing companies. Minutes of that meeting obtained by the News-Sun show the staffing company representatives claim the Haitians were coming here on their own because of Springfield’s affordable living, denying that they were busing people in as city residents alleged.

Reports of human trafficking and exploitation of this population followed.

The city formed an Immigrant Accountability Response Team in October 2023 to investigate, among other things, the staffing companies. In July of this year Rue said the team has revealed the possibility “there were companies that knew they were going to make an effort to bring in individuals who were crossing the border based on federal regulations that they could do that.”

“I’m upset at the fact we didn’t get a chance to have an infrastructure in place if there were going to be 20,000 more people from 2020 to 2025. We didn’t get to do that,” he said.

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Local employers

While it brought challenges, the increased Haitian population buoyed the workforce and the local economy, employers say.

“Our community attracted 7,000 new jobs to the area in the past several years, and we need hard-working, reliable people to fill these jobs,” says a Haitian Immigration Statement on the website for the Greater Springfield Partnership, the city’s chamber of commerce.

“We stand with the city of Springfield and Clark County amid the Haitian population surge to ensure the continued safety, stability and economic success of our community. Businesses are thriving in Clark County by helping (not hating) through collaboration with our members and local leaders,” the partnership’s site says.

Officials with the organization declined to be interviewed, pointing to the statement, which includes this explanation on why Haitians came to Springfield: “They found jobs and available and affordable housing here when they were first entering the United States. Today, most of those jobs are filled and housing is hard to find. We have been working to create more housing options for the entire community for the last five years.”

Ross McGregor, CEO of the Springfield manufacturer Pentaflex and former state lawmaker, said his company chose a staffing agency to help with hiring after vetting to make sure the company was following proper procedure regarding things like immigration.

He said they routinely have Haitian employees brought in through the company.

“There are challenges, particularly with the language barriers. But they come to work every day, they work hard, they want all the work they can get,” he said. “From an employer standpoint, they’ve made a positive impact.”

Chain migration

While staffing companies may have played a role in bringing some Haitians to Springfield, many others were lured here by positive word of mouth. One major draw was the affordable housing.

From a small town “like Springfield” in northern Haiti, Fanfan lived in Florida for two years before coming to Springfield in March 2020. “I had a friend living in Springfield and he talked to me about the opportunities. The cost of living in Miami is really high,” he says. “That’s why I moved here.”

He says it was a struggle at first, and for a month, he lived in a house that he shared with several other people. He then left and lived in Columbus for a year where he worked in construction (Fanfan has a master’s degree in construction management).

Last month, he passed his realtor’s exams and now works with Coldwell Banker. But the timing hasn’t been great, he says, because of the negative things said about the Haitian community.

“The situation right now is not really good because my first target is to help my community,” he says. Fanfan volunteers to greet diners and clear tables at the Rose Goute Creole restaurant on South Limestone Street.

He says that Haitians have left their homeland only because they have been left with no choice. Now he’s here with his wife, mother and sister, and owns his own home.

“I’ve met really wonderful guys. Today, I was at the (realtors) office and one of the brokers told me he is ashamed about the situation,” he said. “I cannot say that anyone has treated me bad.”

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Business opportunity

Others came here lured by business opportunity. Originally from Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital, Jacob Payen lived in Florida for 26 years before coming to Springfield three years ago.

“I got to a point in Florida that I wanted to try something new with my wife. A friend of mine who previously lived in Springfield invited me here,” he says. What Payen saw then was a city with many abandoned buildings and homes, and he thought he could help revive parts of the city.

When he first got to Ohio, he worked for a company installing solar panels. But as he saw the Haitian community grow, he thought there might be other opportunities.

About 18 months ago, he and his wife took the plunge and opened Milokan Botanica, a spiritual and religious goods store, in south Springfield.

“We sell everything from candles to rosaries — anything for your denomination or religious belief,” he says. “It’s been a success since we opened.”

He says that while there are great people in Springfield, some have made threats online and in person at his store.

“A week ago, a gentleman came by, wandering around. We asked him if we could assist him,” he said, “and he told us that we need to go back to our country.”

Payen then says the individual told a second person accompanying him in the store that Haitians are allegedly taking things away from Springfield residents, such as food stamps, which is untrue.

“I see that as a sign of frustration,” he says. “It’s not because they are typically bad people. It’s just frustration.”

The role of government

While no government program directed Haitians to live in Springfield, federal programs expanded by the Biden Administration paved the way for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Latin America, including Haiti, to more easily and legally enter the U.S.

This includes an expanded humanitarian parole program that authorizes foreigners from certain countries to legally enter the U.S., live and ascertain a work permit, and apply for various immigration statuses to extend their time in the U.S.

The programs are meant to reduce the bottleneck of immigrants at the southern border by allowing certain vetted, qualified foreigners to enter America through legitimate ports of entry. The Biden administration told the News-Sun that 520,000 immigrants have been authorized through the parole program in two years. Many of them have been Haitian, though there’s no official estimate.

Once in America, parolees are authorized to live in the states for two years. They can apply for work permits and try for various immigration statuses, including the popular option of TPS — a program created in 1990 meant to provide haven to foreigners in America who would be critically endangered by a return to their home country.

State and local officials have said that most of Springfield’s Haitians are here under TPS. Kersh told the News-Sun that, in her experience helping Springfield’s Haitian immigrants, it’s closer to 50/50; half are on parole; half have been granted TPS. Most are applying for asylum, which can provide a pathway for citizenship and provides protection from deportation even before the case is decided by immigration court.

The programs don’t have pots of money attached to them to help immigrants settle in, nor do they have a wraparound process to supply funds to local communities like Springfield that wind up with immigration influxes that shock their systems. Instead, communities like Springfield have been redirected to other streams of revenue that have largely dried up.

The parole program has humanitarian motives, meant to help Haitians escape an island country where gangs earlier this year controlled 80% of the capitol Port-au-Prince. Gang violence is credited with killing more than 3,200 people in the first five months of this year. Haiti has not had a president since the July 2021 assassination. It last held elections in 2016.

“The reason why I’ve come to this country is because in Haiti there is a lot happening, there’s gangs, there’s (poverty), there’s a politics situation happening, and I want to pursue my career, my goal,” said Petit-Frere.

Petit-Frere said he believes most people in Springfield are good people, but worries about the minority who trade in hurtful, false rumors. “We don’t eat dogs. There’s no way that Haitians are eating dogs. We’re not,” he said.

“We don’t come to America to bring it down. We’re coming to participate, to contribute our services, give our experience. That’s that’s why we are here in America.”

Haitians on TPS may qualify for the same benefits as other Ohioans, such as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, food stamps and Medicaid — with the same work and eligibility requirements.

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Still coming or going?

Former President Donald Trump has pledged mass deportation of Haitian immigrants from Springfield if he wins back the presidency. While he may not be able to round them all up and deport them instantly because they are here legally, he could imperil their ability to stay.

Trump attempted to end TPS in his first term — though the effort was blocked by a court injunction that outlasted his presidency — and has said he would try again if he wins back the presidency. This would mean potentially thousands of Haitians in Springfield would have to leave once their eligibility expired.

The sudden loss of thousands of residents, employees and property owners would have a dramatic impact on the Springfield community.

The Greater Springfield Partnership’s statement notes Haitian workers pay taxes and invest in the local economy, and advocates working with the Haitian community to overcome challenges, aimed primarily at driver education, healthcare, and breaking down language and cultural barriers.

Building community

Inside COhatch Springfield’s coworking and event space, Gilbert Fortil is putting the finishing touches on a new radio studio he hopes will provide thousands of Haitian Creole speakers across the Midwest with updates and essential information.

The 37-year-old, originally from Gonaïves in northwest Haiti, came to Springfield in 2018.

“I think I’m one of the first Haitians here,” he says. “I think that when I came here it was not the Springfield that we have today.” Since 2018, a host of Haitian stores, cafes and restaurants have opened in parts of the city that previously struggled to attract businesses.

For him, the pinnacle of his Springfield experience was Haitian Flag Day on May 18 last year. At Springfield City Hall Plaza, about 50 people gathered as the Haitian flag was hoisted alongside its American equivalent, a sign of the growing ties between the two communities. In Veteran’s Park, Caribbean food stalls lined the grass front. Haitian singers and performers were flown to Springfield especially for the event to entertain the crowd.

“Everybody came together to celebrate with us,” he recalls. “That for me was a very great moment.”

But it hasn’t all been positive.

He recalls being in a Family Dollar store two weeks ago and seeing a female customer say something bad to a Haitian man who was in the store at the same time. “It was very sad. I don’t want to repeat what she said,” he says.

“They are afraid. All Haitians are, to tell you the truth. They don’t know what will happen after the election.”

However, he says he has only received positive messages from American friends.

“The reason I created this radio station was to have a place that you can come and introduce ourselves,” he says, “tell people exactly who we are, tell people we can live together.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.