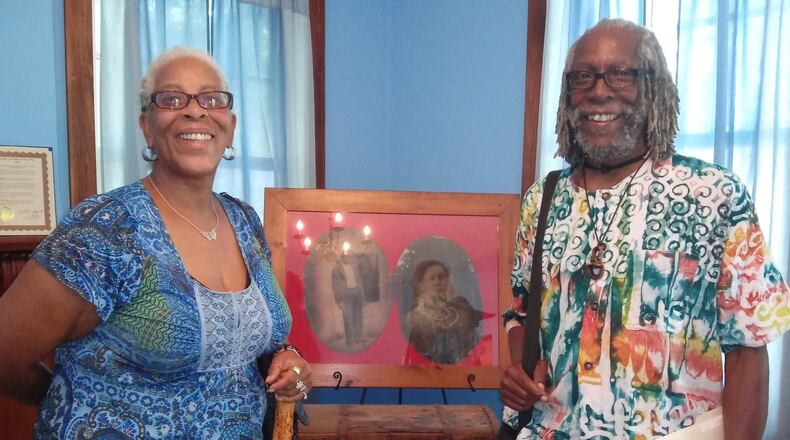

The items themselves are modest, everyday objects — a trunk used by White’s second wife, Amanda, when she headed north from Kentucky to Springfield, Ohio, where she would cook for the president of then-Wittenberg College, and a portrait of her and her husband. The trunk also held a Bible from what’s believed to have been one of the area’s earliest First African Methodist Episcopal churches.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD

• Springfield man to be honored for work with former inmates

• They have a racing team, a driver and a logo. It’s all fake (except the fun).

The delivery of the items had been talked about for some years. Springfielder Shari Booth, a great-great granddaughter of Addison White, had talked with Betty Grimes and Barbara Dye, early movers in the Gammon House project, about the artifacts. She then called her brother John Booth, who lives in Yellow Springs and knows Dano Grimes, Betty’s son, through a mutual interest in music, who also was interested.

Years then passed until this spring’s election, when Dale Henry, who now chairs the board at the Gammon House, ran into Shari Booth by chance at the polls and she said “Let’s get this thing done.”

“We could never get all my siblings and everyone to agree,” she explained. “This time we got it together.”

The objects are on perpetual loan to the Gammon House, to be returned to the family only in the event that the museum encounters unforeseen problems.

Nobody’s happier with the transfer than John Booth. “It’s better than having it sit in my garage,” he said of the trunk – and not just because it was taking up space. “We can share it with the world.”

The transfer of the objects to the Gammon House Museum is a symbolic crossing of paths of two men who made national news during the days when the country’s attention was focused on a border called the Mason-Dixon Line, earlier on because it was being crossed by escaping slaves, later on when it was crossed by invading armies.

Now 63, John Booth became aware of his family’s legacy only slowly while growing up in Mechanicsburg.

“We were studying the Civil War in middle school, talking about slavery, so I asked my grandma what’s the real deal on the Underground Railroad.” Although he’d heard some story about it involving Champaign County, Booth had no idea of his connection to it until his grandma said “that was my Daddy.”

Booth also found himself in trouble one day when friends came back from the Champaign County Fair wearing Union soldiers’ caps and he removed one that looked just like it from his great-grandmother’s trunk.

“I caught it for that,” Booth said, though not quite as much as the memory of one of his aunts by marriage took most of the items from the trunk one day and burned them, saying “We don’t need to keep all this slave stuff.”

Shari Booth has recollections of the family story from earlier in life.

“When my Grandma was alive, my bedtime stories were about her Dad,” she said. One of the most striking was her grandmother’s recollections of rubbing Addison White’s welted and scarred back with ointment to relive the soreness he felt in old age from the whippings and beatings he took as a slave in Fleming County, Ky.

Her favorite, however, involved White’s shooting and wounding a federal marshal who had come to a farm outside of Mechanicsburg intending to return White to his owner on May 21, 1857.

“That always tickled me, because he was such a rebel,” she said.

Both John and Shari Booth are charmed by the personal and romantic story of how while passing through Cynthiana, Ky., an escaping Addison struck up a conversation with Amanda as she was snapping beans, never imagining that the two would ever meet again, much less marry.

The federal officers’ pursuit of Addison White to the Champaign County farm of Udney Hyde, and the physical, political and legal battles it sparked between federal, state and local authorities is much heavier stuff. Front page news across the nation in the years leading up to the war, it involved the beating of Clark County Sheriff John Layton, from which he never fully recovered; a pitched legal battle that had Ohio challenging the federal government’s authority in the case; and an out-of-court settlement negotiated by Ohio Gov. Salmon P. Chase, later a member of Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet and a U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

That story will be the subject of next week's column. (Those who are impatient can read a related column I wrote titled "Clark County Sheriff was felled by federal marshals".

If the Booths’ knowledge of their great-grandfather’s history came to light during their childhood, the significance of the home free African-Americans George and Sarah Gammon built in 1850 on Piqua place has gradually become more familiar to the Springfield community.

As the website gammonhouseoh.org points out, the risks they ran were substantial. The Fugitive Slave Act adopted by Congress in 1850, imposed stiff penalties for anyone aiding or abetting an escaped slave: six months imprisonment and what the site correctly describes as “a massive $1,000 fine.”

Not surprisingly, their son, Charles, a painter by trade, traveled to Massachusetts to join the 54th Regiment. (Regiment records list White as a salt maker.) Other Springfield natives who served with the unit.

Neither Gammon, a 25-year-old painter when he enlisted, nor Albert Evans, a 28-year-old machinist, returned from service. Both were killed in the attack on the July 7, 1864, attack on Fort Wagner depicted in the 1989 movie “Glory” and much celebrated at the time by the Union Army as the first major engagement involving African-American troops.

Two other Springfielders in the unit were wounded during their service, 22-year-old carpenter Charles Goff in the same attack and Robert Smith, a 36-year-old brick maker, who was accidently wounded July 7, 1864, at James Island, S.C. Christopher Hart, a 22-year-old waiter, and Joseph Meeks, a 20-year-old shoemaker, both served from May of 1963 to August of 1865 and were honorably discharged with Goff, Smith and, of course White, who returned home to work at the street maintenance department in Mechanicsburg.

His choice of work may have been, in part, a way to, in modern terms, give back to the community that helped to prevent his return to slavery by raising $950 for his freedom and the languishing of charges against his neighbors who came to his aid.

John Booth said the man who once had been owned by another “did not like the idea that he owed anybody for anything.”

About the Author