Contraband refers to enemy property seized in war, and, in the Civil War was applied to escaped slaves. Although abolitionists insisted on the term “refugees” to avoid defining people as property, Taylor said, but they were in the minority.

Given a chance to return to the story of “contrabands,” she found evidence for the fascinating and largely untold story described in the title of her awarding winning book “Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps.”

Five hundred thousand slaves – 1 in 8 of the nation’s 4 million -- escaped during the Civil War, Taylor said.

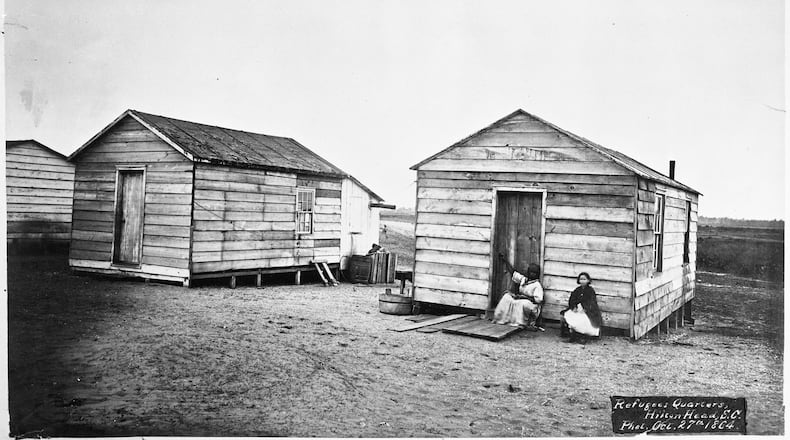

Almost from the outset, they established “large clusters of hastily built shacks and cabins … inside the lines of the Union Army.” There, they were put to work doing the same kind of task slaves were doing for Confederate armies.

“They built roads, they dug ditches, they buried bodies,” Taylor said.

“Some (women) went to work as cooks and as laundresses. Others worked as guides and sometimes even spies for the Union army,” due to their knowledge of the local landscape.

Although camps established along rivers often lasted only until the next flood, Civil War era photographers recorded of a wide variety settlements, images of which appeared in Taylor’s Power Point presentation.

The settlements ranged from a hastily assembled tent city on the outskirts of Richmond, Va., at war’s end; to simple cabins on Hilton Head Island, S.C.; to what looks like a subdivision of platted houses at the Home for Colored Refugees at Camp Nelson, Ky.

They took root elsewhere, too.

In Giles County, Tenn., Taylor said, “There were 63 people who had been enslaved on one plantation. But a few years into the war, there were 1,400 people living there in 240 newly built houses.”

Taylor found 300 settlements in all, some of which “became like new villages of freed people” -- people savvy enough to hire an attorney at war’s end they should be given the land once owned by Confederate “traitors.”

Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s land was indeed confiscated for that purpose, Taylor said, but the land of less politically and militarily prominent Southern owners was returned to them in the first of a number of decisions that forsook the interests of former slaves in the name of national reconciliation.

That reconciliation likely seemed premature to slave refugees attacked during the war by Southern troops that “set their sights on these camps” because they “embodied this social revolution (in pursuit of) freedom for enslaved people that (Confederates) were fighting a war to prevent.”

In the process of sketching out the scale of the settlements, Taylor unearthed details about the day-to-day lives of refugee slaves, among them Eliza Bogan. Following her husband’s death from measles in a slave refugee camp in Helena, Ark., Bogan managed to stay alive the refugee communities while exposed to “threat of violence and illness” involved in being near Union troops. All the while she experienced freedom and found purpose in a way that transformed her life.

Taylor says Bogan’s story “reveals a lot about how becoming free in the war could require living amid active combat and having to fight for… survival just as a means to become free.”

Finding such stories was a battle itself, she said, largely because of “what’s not available” in the historic record.

Historians gravitate to “any kind of diary or first-person journals,” Taylor explained, because people’s own words are the best windows into how their experiences.

But because it was illegal to teach slaves to read or write, words written by slaves were in scant supply. That had Taylor in the stacks of the National Archives amongst the copious records kept by Union Army clerks.

Refugee slaves Emma and Edward Whitehurst, are first mentioned by clerks at Newport News, Va., then at Fort Monroe. Through the war, Taylor learned, the Whitehursts rented a horse from the army and worked in the army hospital.

“In the battle of Big Bethel, there in June the 18th, ‘61,” Taylor said, (Edward) “worked as a guide” for Union troops.

Two months later, “both exercised their new right to quit their jobs, which was something they could never do in slavery, and do something else which surprised me .… Opening a store was not one of the first things I thought somebody coming out of slavery would do.” In a risky move, “Edward went back to their original plantation .. and collected some of the harvest of the crops that they had grown and brought that in to sell at the store.” Army records also report the Whitehursts’ efforts to recover money from the Army after Union troops took some their goods without paying them.

“Their story really reveals a lot, I think, about how enslaved people just tried to get on their feet economically after they left slavery. And it was a struggle.

Although Taylor says the vignettes she has assembled about the Whitehursts’ and others can’t be fleshed out by personal testimonies, “I think they would find it recognizable.”

And, taken together, their stories “tell us a lot about how emancipation and freedom came about,” including “the great risks that hundreds of thousands of people took to become free.” That, she said, “tells us about the role that African-Americans themselves played in securing their freedom.”

HOW TO WATCH

To view Amy Murrell Taylor’s entire presentation on slave refugee camps in the Civil War, go to https://cutt.ly/dramt. The video is available courtesy of the Clark County Heritage Center’s annual Springfield Civil War Symposium.

About the Author