On June 14, the African American Community of Funds of the Springfield Foundation will honor Mims at its annual banquet for the work he has done trying to help former offenders from being shaken by the same sound.

Doors will open for the event in the Hollenbeck Bayley Creative Arts and Conference Center at 5:30 p.m. Admission is $30, and tickets can be reserved online at SpringfieldFoundation.org.

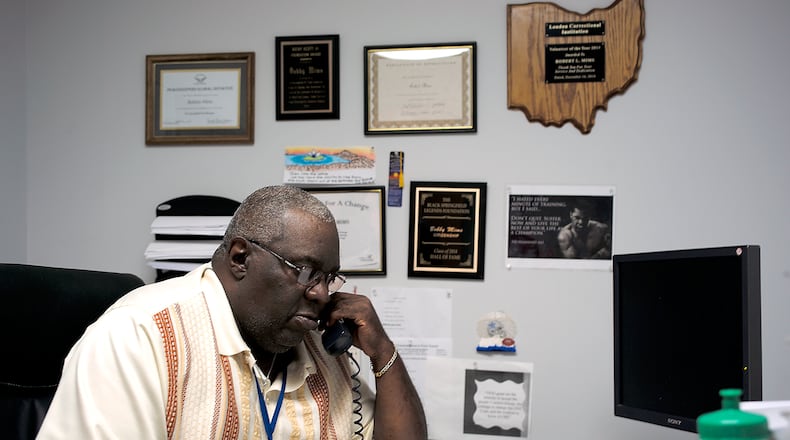

Mims, the 73-year-old Director of Re-Entry Services for OIC of Clark County, said the essentials of incarceration haven’t changed. “Prison is prison. I don’t care if you were in prison in the 1960s or 2000.” But when he was released in 1970, there weren’t any programs to help inmates make the transition to community life. Luckily for Mims, he had by then established clear goals for himself.

One reason, he said, was the length of the sentence he served.

“I’ve said this many times, and I mean it. I am glad that the judge gave me the time he gave me. It took me about four years to get my mind right and to get me to do something with my life I needed to do.”

Time was not the only factor. So was the accumulated weight of his mother’s monthly visits. “I would see that disheartening look on her face, because she didn’t raise me that way. And that hurt me. Then when I got home, the talks with my dad (were important), letting me know that if you’re going to make it in this world, you have to work. He was my heart.”

Once he decided he wanted to be a social worker, Mims knew he had his work cut out for him. Although regulations of the time did not allow convicted felons to do social work, Mims took steps in that direction through college classes offered in prison. After his release, he went to Wayne State University in Detroit to finish his degree.

But it was awhile before he had the chance to use what he had learned. Mims’ said his first good job after prison was with Springfield Metropolitan Housing Authority, where he worked for eight years. He then worked with the Springfield Urban League for five years, during which time he met Mike Calabrese, executive director of OIC.

Calabrese then hired Mims at OIC, where he first worked in youth programs, then landed a job as a job coach. About that time, he and Ronnie Hill, a former offender and Mims’ friend, told Calabrese there was “a big disconnect” between the community and prisoners returning to community life, some of whom came to OIC for job training.

Calabrese lined up the required money and support, “and things kept growing from there,” said Mims, eventually leading to the current program that works with 200-225 men and women a year in facilities, among them: London Correctional, Madison Correctional, the Ohio Women’s Reformatory in Marysville, Dayton Correctional Institution, Pickaway Correctional and the Clark County Jail.

Mims said the overall program’s several aspects took time to organize. One involved persuading Springfield businesses to give inmates a chance at what he calls “good factory jobs,” something they were willing to do. Another involved building a community coalition of all who provide services that might help inmates deal with problems that landed them behind bars and reduce the likelihood that they would re-offend.

McKinley Hall and its drug treatment programs are among the resources that can help inmates make changes. But change cannot happen, Mims said, if the person who needs the help doesn’t see the need.

“It’s very important that the person themselves realize what problems they have so we know what to address. Alcohol, drugs, anger management – before you start talking about other steps, you have to learn to control the problem.”

“That’s why getting connected with them in prison is important,” Mims said. It’s something he and others do through the Think for a Change Program and locally in the Clark County Life Skills program in the county jail, and that Mims says is a big factor in the effort’s 80 percent success rate.

The programs provide staff with time to establish trusting relationships with inmates, get a sense of someone’s background, and assess what problems may arise in working with them upon their release.

Class participation, what the person says in conversations or when challenged – all these things help to determine their willingness to work and change. It also gives social workers a sense of who is serious about the program and who “is just spinnin’ you,” Mims said.

“The big thing about being a social worker is you’ve got to have a mind and an open heart, and you’ve got to know which one to use when.”

“Because I’ve established credibility with the (Ohio) Parole Board, the judges and the probation departments, I have to be very careful,” Mims said. “I don’t want to go in front of the state parole board (speaking in support) of a person and find out they’re doing the wrong thing.”

Mims has learned to pick up on signals that help him read an ex-offender’s situation. “It all starts with who’s picking them up” on the day of release, he said. “You can almost tell how things are going to be.”

If a mother, father, professional or church member is involved, that’s a good sign, Mims said. “If it’s a sister and her (sketchy) boyfriend,” he said, “there’s trouble by the time they hit I-70.”

“I’m not saying we can’t help them,” Mims said, “but it’s not as easy.”

Nor is re-entering the community, he said, which is why inmates need support.

“Coming out of prison, you really feel at loose ends. You don’t know how you’re going to be accepted. You don’t know who’s in your corner and not in your corner.”

Situations tend to be more complicated if the victim of the crime that caused the incarceration is a family member. Some people released from prison believe they’ve paid their debt to society and all should be forgiven or forgotten, Mims said, “but it doesn’t work that way” for victims of their crimes.

Expectations of those who have been supportive during a lengthy sentence also can be obstacles. Pressure on the returning person to immediately start making money and contributing to the family can be disastrous.

But before going to work, Mims said, inmates have to address the problems that landed them in prison. His question to family members impatient with delay is this: “Do you want him for six months or six years?”

Mims has developed other sayings. To encourage good habits, he says, “If you train the body, the mind will follow.” To encourage thoughtful decision making, he paraphrases legendary basketball Coach John Wooden: “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.”

But whatever support he and his staff and the community provide to help people learn to take responsibility for their own action, there’s a point where the individual has to take the final step. “I’ve always said to people: You have to teach yourself to be the person that you want to be.”

Teaching himself to do that is one reason Mims, who has six children and has given up on counting the number of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, will receive an award June 14. It’s also a reason he won the 2015 Gary Mohr Award as the best director of a re-entry program in Ohio.

But his ongoing reward is his work.

“I enjoy it. I really do. If I wake up one morning and all of a sudden feel like I’m not making a difference, I’m not being effective, I’ll retire the same day.”

Otherwise, if his health allows, he’ll be at it until January of 2020.

That’s clearly the smart bet.

About the Author