As Russo’s mother had often told her, Aunt Maud not only had founded the Columbus Avenue church, but had been a missionary in West Africa during the 1920s, once having killed a large snake in a child’s room with a chunk of wood and exchanged pleasantries with head hunters and cannibals encountered in the Sierra Leone countryside.

More Tom Stafford:

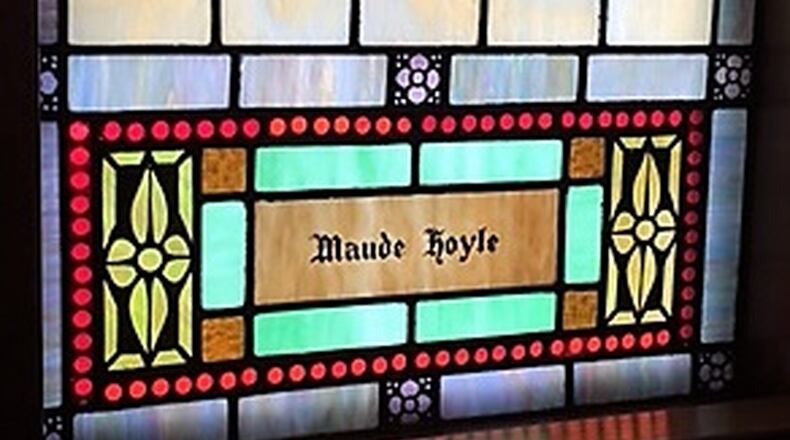

Four years ago, as she began working in earnest on “Beautiful Feet: The Story of Maud Elizabeth Hoyle”, Russo wondered whether the narrative would run more than 20 pages of accumulated family legend and saved copies of the Rev. Hoyle’s sermons. Fortunately for her family and local history, Russo leveraged the research skills she developed as a professional librarian to pry open the stained glass window of history and connect the charming stories she inherited with the real person whose faith helped her face what today’s missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers still encounter: The limitlessness of need in a poverty-stricken world.

Supplementing a 113-page narrative are 70 pages of the Rev. Hoyle’s writings, in which her voice comes alive as if from the pulpit, along with the appendices, end notes and bibliography that document the authors’ considerable and well-considered research. Available in paperback in the pedestrian typeface of Amazon’s self-published books for $8.95, Beautiful Feet also is available in a Kindle edition for $4.95.

Begun in Springboro Dec. 18, 1881, the third child and first daughter of Stephen Ursheline Hoyle and Ida Virginia Dowden Hoyle, Maud’s life both nearly ended and took on a new direction, when, as an infant, she nearly died, and her mother, in a desperate prayer, promised to dedicate the child’s life to God if baby Maud survived.

The following year, the family moved 25 miles north to Trebein, where her father worked in a mill and a second daughter Charlotte, called Lottie, was born. The family attended the Reformed Church at Alpha, now the Beavercreek United Church of Christ, and the one-room Alpha School. There was also twoolder Hoyle Boys, Walter and Wilbur.

In the fall of 1893, 12-year-old Maud and her family moved to five acres on Columbus Avenue, where they established a truck farm, selling their goods in stall 76 of the City Market downtown, where their white celery was a favorite. Russo here adds charming details: that Maud memorized the Bible while planting potatoes, and that she dressed chickens and made corn mush and hominy sold to help the Hoyles make ends meet.

MORE TOM STAFFORD:

The children attended the Benson School in

in the A.B. Graham era of the Springfield Township Schools. Russo’s meticulous research, unearthed the facts that Maud, in 1897, and Lottie, in 1900, were two of the three students of Benson School who in a 10-year period passed the Boxwell-Patterson Exam, which gave them the opportunity to continue their education without charger after eighth grade – opportunities the family with limited means chose not to take advantage of. (A copy of the difficult exam is included in the book’s appendix.)

Presumably to make ends meet, the family also took in borders, one of whom was remembered to have coughed excessively after youngest daughter Lottie was stricken with the tuberculosis she died from on Feb. 27, 1904, at age 17.

The family leaned on the faith they’d continued to develop at the Lagonda United Brethren Church, a stone’s throw from the McCormick Reaper plant where the boys by then worked. Maud, an early participant in the church’s I Am His (IAM) Club advanced her education by gaining accreditation from the Sunday School Association as a teacher on March 31, 1905.

The next year, at age 25, she continued on the path of faith her mother had set her on by entering the Union Biblical Seminary in Dayton, where, Russo tells us, a bell that had been hauled over the Allegheny Mountains was rung at 5 a.m. and 9 p.m. each day to open and close the seminarians’ day.

One of four women in her class of 12, Miss Hoyle clearly expressed her views. In a 1907 thesis titled “Practical Christianity,” she wrote of Christianity like a woman on a mission: “The test of true religion is its power to help, to relieve suffering and to transform lives. The substantial essence of religion does not consist in deep experiences, but in duties performed.”

That point of view is echoed in a later sermon, “The Love of Christ to his People,” in which she offered a lesson in living theology: “Men of the world do not read God’s word to find out what is religion. They look to the live and conduct of those who profess to believe in it.”

Seminary records Russo uncovered indicate that, upon graduation, her great aunt hoped to attend Starling Medical College (one of the forerunners of Ohio State University’s medical school), “to prepare for foreign missionary work.” But after the quarterly council granted her license on June 11, 1908, which the book notes as the last time the Chicago Cubs won the World Series for more than a century, the Rev. Hoyle instead went back to her home congregation to be assistant pastor – and to her family to help out.

Four years later, her pastoring had leveraged interest in people along Columbus Avenue to first establish a Sunday school and then build a new church at Columbus Avenue and intersection Pumphouse Road. As pastor and leader of the all-female finance committee and pastor of the Columbus Avenue United Brethren Church, she turned the first shovel at the groundbreaking on March 4, 1912.

Like many other church buildings in those days, this one was largely built with volunteer labor. While the founding pastor proudly noted that in her version of the early church history, the Rev. A.J Furstenberg later tacked on something the Rev. Hoyle left unsaid: “Had it not been for the untiring efforts of (Maud Hoyle), there probably would be no history to write.”

But in 1917, having founded the congregation and doubled its official membership, she again felt a call to foreign mission work and prepared by enrolling as one of 45 students at the Springfield Nurses’ Training School at Springfield City Hospital, located on Selma Road at East Street.

MORE TOM STAFFORD:

Author Russo here shows both her resourcefulness and integrity as a researcher. While she was able to establish through local records that 90 percent of what was taught at the local school involved “practical learning” of hospital tasks, also she provides readers with a sense of the nursing education of the times by quoting the National League of Nursing Education’s Standards of that era — though clearly noting her inability to confirm that those standards were used in the Springfield training program.

First-year students, the standards say, were required to do the dirty work of nursing — “certain of enough tasks, naturally perhaps distasteful or repulsive, to get finally rid of whatever inhibitions or repugnances (sic) she may feel towards them.” The passage ads: “If she retains them, she had better seek her vocation elsewhere.”

In the coming years, Maud Hoyle would confront “repugnances” and stark cultural differences of the likes most of her classmates would never have imagined and that Maud herself would struggle with while answering her call to mission in Sierra Leone West Africa.

Next week: Part 2 – Mission Improbable: Martyrs, head-hunters and witches on the West African Frontier.

About the Author