But the drinking fountain labeled “colored” was one of the sights I most remember from an early 1960s visit to Washington, D.C.

I was grade-school age the summer we pulled into that Maryland rest stop, and the experience has confirmed for me something my parents, who were teachers, often said: That travel is one of the best ways to learn about the world.

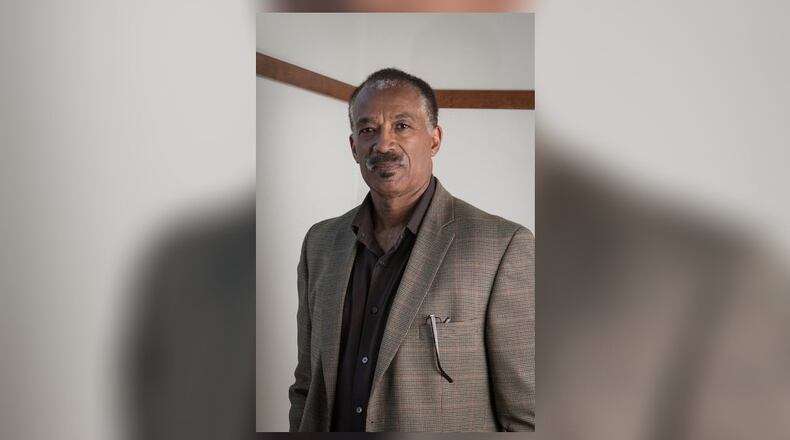

The memory stepped forward last week after I’d had coffee with Springfielder John Young as he told me about his approach to talking about race. His method involves sharing stories about moments in which race came to mind for us.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: Swapping stories about race opens door to real conversation

Like my parents, he has been a career teacher, with most of his years spent at Wittenberg University. And to him, story-telling is a teaching method - one that encourages us to teach one another about the world as we see it.

Which brings us to another story Young told me from a time when he was the age I was when we pulled into that rest stop.

It, too, happened in Maryland, and its main character was Cowboy, a white policeman who walked a beat in Young’s West Baltimore neighborhood.

“We called him that because most policemen carried their guns high up on their hips in those days,” Young said. “His was just a little bit down.”

Cowboy came walking down the street one day when Young would rather he hadn’t.

“We’d make a slingshot out of a hanger and some rubber bands,” he explained, and would ”shoot staples at targets.”

That, of course, was frowned on.

But as Cowboy approached, Young was dealing with a self-inflicted wound that kept him from just waving and turning away.

The staple from Young’s slingshot “came back and hit me in the stomach,” he said.

So, Cowboy caught him with a slingshot in his hand, blood on his shirt and a distressed look on his face.

Aware of where the real court in Young’s life was in session, “he walked me to my house, knocked, and my mother answered the door,” Young said. “Boy, did I get in trouble.”

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: Escape from the turmoil is not an option when you care about the world

But he always kind of liked Cowboy.

That wasn’t true of a couple of other white cops who chased him and his friends off the street, where they had been playing football. It wasn’t so much being flagged that bothered Young. It was the way the white policeman jumped out of the car using profanity to tell the kids to get their football and get out of the street.

That memory is mixed with another impression from the time: That as patrol cars began to replace cops walking beats, the black cops seemed to stay on foot while the white cops rode in the cars.

Fast forward a few years to the summer of 1980.

By then a graduate of Baltimore’s Morgan State University, Young had been accepted to graduate school at the University of Dayton and landed a summer internship with the Baltimore city government.

The internship involved riding with the police in various of the city’s districts. And while waiting in a satellite mayor’s office for his daily ride, Young spotted a research paper by a Johns Hopkins University sociologist.

The sociologist, who had ridden with the police for a year, reported that some referred to blacks as “apes” and “Zulus” and that some also said the city should put a fence up around the neighborhoods and let the black people kill one another.

Young wondered if the one black cop he rode with that summer was aware of that.

Then another story came to his mind.

Young asked whether I remembered a guy named Tom Snyder, and I do. He was an incessantly smoking host of a news and commentary show called “Tomorrow” that came on at 1 a.m. back in the 1970s, just after the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

In the way I recalled the “colored” drinking fountain, Young recalled a night on which Tom Snyder went underground with family of American neo-Nazis. As most parents do, the father and mother had passed their values along to their growing children, each whom had set professional goals to become police officers, so they could beat up black people.

This was 50 years ago, of course. And after the 1968 Baltimore riots, Young Tommy D’Alessandro, whose father had been mayor before him and whose sister is House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, set new requirements for the department’s officers. And that, too, was 50 years ago.

But a resurgence of white supremacist groups in the country has Young remembering that episode of Tom Snyder. And he worries about the power police unions have to protect them.

MORE FROM TOM STAFFORD: Rosebuds blossom again: Invitation allowed drill team to step out of the past

A final thought about something I’ve learned about swapping stories with people from different backgrounds: That sometimes, though the particulars are different, essences of the stories we tell are the same.

As I’ve told you in this spot over the years, being a journalist has been a continuing education in my own sense of ignorance and prejudice, which is why it has been such pleasure.

Over the years, my ignorance has been lessened by all the people I’ve interviewed and talked with, and everything I learned. My prejudices have been curbed by what I’ve learned and the wide variety of people who have taught me.

Young’s face showed slight displeasure when I used “ignorance” and “prejudice.”

So, he removed my purposely loaded words “ignorance” and “prejudice” and cast the thought in the more positive and encouraging language of a teacher.

“As long as you live, you’re always going to be educating yourself.”

To a son of two teachers, that has a familiar ring.

This is the second of a two-part conversation with former Wittenberg professor John Young about race. Part I published in this space on Sunday, June 21.

About the Author