It would allow local governments to be part of the settlement process even if they are not plaintiffs in ongoing litigation over the toll that opioids have had on communities across the state, said Jill Allen, the law director for the City of Springfield.

As of last month, more than 150 Ohio local governments are part of a consolidated case pending in U.S. District Court before Judge Daniel Polster in Cleveland. However, local governments do not waive their right to file a separate legal case by accepting the One Ohio memorandum of understanding, said Michelle Kranz, an attorney with the law firm Zoll & Kranz, LLC, who will provide legal counsel on the case to Clark County.

MORE: Navistar reports net loss of $36M for first quarter of 2020

Clark County Commissioners approved a resolution on Friday to retain her firm’s services to assist them in the “pursuit of civil litigation and/or settlement to abate or cause to be abated the public nuisance” caused by the opioid crisis in the community.

Clark County Commission president Melanie Flax Wilt said those services are related to the terms of the “One Ohio” agreement as each locality involved would receive a certain percentage of the settlement.

“Our community has suffered greatly from the opioid problem. We need to recover costs that were lost during that time and position ourselves for better days ahead,” she said. “Anything that we can do to improve prevention and education for those that are suffering from addiction as a result of this, that is a positive thing for our community.”

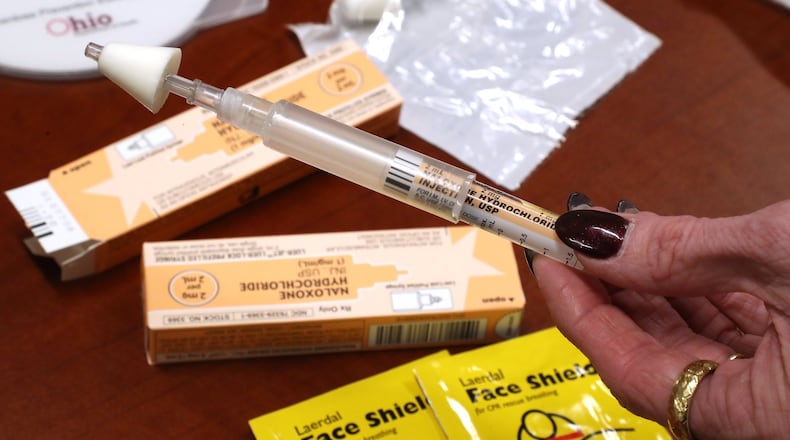

In 2017, deaths resulting from drug overdoses peaked , according to data from the Clark County Combined Health District. There were 106 overdose related deaths in the county during that year.

This news organization previously reported that more than 2,600 lawsuits were filed against opioid makers and distributors, which many U.S. communities blame for fueling the epidemic.

The argument for One Ohio is that it puts the state and local governments in a strong position and it’ll give local governments a say over how settlement money is distributed and spent.

However, it is unclear how much money would be awarded if a settlement is reached. Under the One Ohio agreement, 11% would account for attorney fees and the remaining money from a settlement would be divvied up — 30% for local governments, 55% to a new nonprofit foundation and 15% to the attorney general’s office.

MORE: County health districts, schools work to prepare, prevent coronavirus

This newspaper previously reported that the foundation would be controlled by a board consisting of 25 members appointed by state, legislative and local officials. It would spend settlement money to address the opioid epidemic both locally and statewide. Those funds could also be used to support research as well as education regarding opioids.

Each local government involved will receive a specific percentage of the money from the 30% that will be divvied up to communities across the state. A specific entity’s share is determined by several factors including how opioids were distributed or sold in an area, other complications caused as well as deaths attributed to the opioid crisis, Kranz said.

The State of Ohio is expected to go to trial regarding its litigation in October. Though the goal is to reach a settlement before then, all parties involved in the case have to be willing to agree on the terms, said Frank Gallucci, an attorney with Plevin & Gallucci, who has worked with local governments on opioid cases.

Kranz said if a settlement is reached, those involved with the settlement would have the choice of either accepting or declining the terms of that agreement.

About the Author