DETAILS: Hundreds flock to Springfield vigil to stand against hate, racism

Earlier this week, Springfield Mayor Warren Copeland spoke out about the recent violence in Charlottesville, Va., that saw three people die and 19 injured amid violent protests.

And more than 250 people attended a vigil in downtown Springfield on Wednesday evening in light of recent events — and stressed Springfield won’t stand for the hatred and racism shown during the protests in Virginia.

White supremacists have held rallies in downtown Springfield — most recently the 1994 KKK rally, which didn’t lead to any violence.

RELATED: Springfield mayor speaks out about Charlottesville violence

Here’s an excerpt of the News-Sun’s coverage of the event:

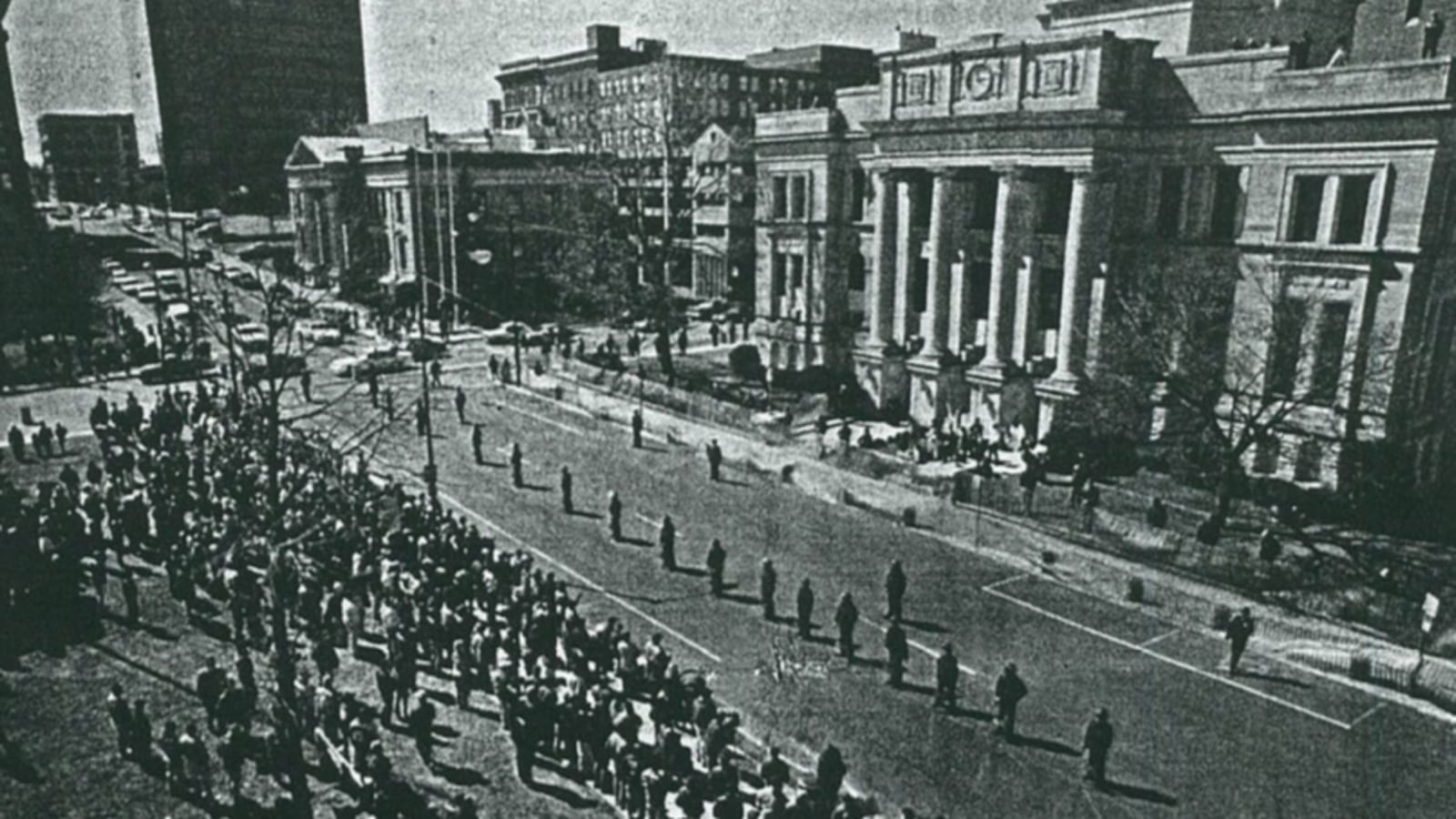

An immovable line of law enforcement officers and restraint by area residents defused a Ku Klux Klan rally Saturday into a war of words by extremist groups.

A group of out-of-town Klan haters slowly trampled a plastic snow fence and moved within inches of Springfield police in the middle of Limestone Street. The inch-by-inch movement by the opposition group came near the end of the rally in front of the Clark County Courthouse.

But the silent officers, clad in helmets and carrying shields, stood firm and the verbal confrontation never became physical. The violence often associated with Klan rallies never happened, largely due to textbook law enforcement crowd control strategy.

“They were rocks. When the fence went down, they didn’t budge an inch. They didn’t engage those people or start talking to them,” Springfield Police Division Chief Roger Evans said. “This was the first time many of our guys had been exposed to this kind of tension. They did one wonderful job. I’m proud to say I’m chief of all those people.”

Fifteen members of the Knights of the Klu Klux Klan, dressed in black and white with Nazi-like swastikas on their shoulders, stood in front of the courthouse to deliver their message of white power.

Authorities anticipated at least 1,000 spectators but only about 300 people attended. No one was arrested or injured during the one-hour rally, according to city officials.

While the protest was mostly non-violent, residents had differing opinions about the law enforcement’s presence at the event:

Keith Robinson, 36, of Springfield, held his 6-year-old son on his shoulders while Klan protesters shouted what he called “messages of hate.”

“I wanted my son and daughter to see what happens in the world. I’m black, my wife is white and we have mixed children,” Robinson said. “Color is good and we have too much hate in this world as it is.”

But 17-year-old Mark McWhorter, also of Springfield, said he and his friends wished the police would step aside so they could “get” Klan members.

“We’d love to beat the (expletive) out of them,” he said. “I can’t believe they guard these guys and let them do this in the middle of town. We’re black and six black people can’t even walk down the street in Springfield without getting harassed.”

Similar to the events in Charlottesville, many people from out-of-town came to both protest and oppose the protesters, according to another story from the News-Sun archives. The National Women’s Rights Organizing Coalition, a Michigan-based group, came to stop the rally, planning to use force. This is how one resident reacted to the event in the story:

Michael Smith watched Saturday morning’s Ku Klux Klan rally with disgust. The 18-year-old South High School junior saw Klan members shout racial slurs at a crowd of about 300 as Klan opponents screamed obscenities and inched toward police lines.

When it was over, Smith called the event “crazy.”

He first mentioned Klan members who set up microphones and flags and verbally attacked the crowd on a makeshift public address system.

“They do that to make themselves look bigger,” he said, referring to the Klan’s penchant for insults and inflammatory rhetoric.

But he also was disgusted with members of the National Women’s Rights Organizing Coalition, a group that follows the Klan around the state to shout them down.

“These people shouldn’t do this either because they come down here and make the Klan feel bigger. They give the Klan their power,” he said.

The News-Sun’s editorial board said the event would simply be “a footnote” in the history books:

What could have turned into one of the uglier chapters of Springfield history will end up instead in its deserved place — a small footnote because of the good judgment displayed by our community.

When people pull up copies of the newspaper on their computers 30 or 40 years from now, they will not read about bloody fistfights and ugly confrontations between Ku Klux Klansmen and opponents on March 19, 1994.

They won’t read about rage and hatred.

They will instead read about a Klan rally that ended up to be not much more than a shouting match between two out-of-town radical groups. They will read that the Klan, and a bitter opposition group, were allowed to exercise their right of free speech and assembly before taking their message to another community down the road.

They will read that Springfield and Clark County residents kept their cool and refused to be drawn into a violent confrontation with Klan members.

About the Author